Mapping the Underworld - Part One

An introduction to the terrain of divergent bodies & beings, experiences & events

There’s an image that haunts me. I came across it in Wayne McCrory’s 2023 book, The Wild Horses of the Chilcotin. It’s a picture of a wild mare in an advanced state of laminitic crisis. She’s rolled back practically on her fetlocks—her legs presumably grown so deformed they’re unlikely to recover. It’s hard to imagine how she’s still alive—such is the imperative of four feet that can hold weight and support movement to the survival of an equine. It would have taken those legs a fair bit of time to get that way. And yet, somehow, she’s still going.

Some will only see slow death and suffering in this image. Few will contemplate that, to the mare, this is just the way things are. And in traversing the purgatorial wasteland towards inevitable demise, she might still have had access to fleeting moments of joy, might still have provided life-giving sustenance to a little one, might still have played a vital role in her herd bonds, might have contributed to evolutionary consciousness by logging her clever movement improvisations in the genetic memory of her kind, might have stood in the sun and experienced bliss.

Let me pause here. Those are heavy first paragraphs to process.

But I assure you that the discomfort you might be feeling—the discomfort I feel in describing her plight to you—this is the first sign that you’re entering the underworld of which my title speaks.

If you’re thinking of leaving on account of the heaviness, please don’t go so quickly. That feeling is but an acclimation symptom. The atmosphere is dense in the underworld. But that alone is not a reason to flee. I promise you, this terrain contains gifts and lessons, insights into adaptive phenomena, invitations towards alternative modes of perception. And yes, sadness and uncertainties, inconveniences and what some would call tragedies as well. You stand at the trailhead of an uncharted territory and your discomfort is the deer path in.

Let us be cartographers. And let the sensations that we habitually avoid be our navigational equipment. Those conditioned feelings have been limiting our sense of self and the size of the world we inhabit. Let us bravely sit with the discomfort and see where it takes us.

And the first place it takes us is back to the wild mare. Her image haunts me not only for the obvious reasons, but because it challenges our idea of the order of things. Are we not sold the notion that the wild takes care of the misfortunate so as not to prolong their suffering? Do those bodies that no longer function as they should not become susceptible to predation by carnivores? And in wondering how she’s managed to tend to herself for sufficient time that those limbs have become so misshapen, how do we not then simply conclude: nature is cruel? How do we not then simply pity the privation of wild things with no recourse to medical care and recuperative interventions? With nothing but reliance on the slow mercy of predators who are too preoccupied with other things to fulfill their ethical duty as clean-up crew in our tidy narratives of life outside civility.

Nature is cruel.

Nature is privation.

Nature has her in-built mercies.

These are the narratives from which we have to choose to make sense of wild mare’s predicament. But aren’t these narratives a bit limiting? Mightn’t there be alternative modes of meaning-making to naturalize realities where suffering isn’t an opt-out selection? Mightn’t there be alternative modes of meaning-making to explore and explain how she’s still living while she’s supposed to be dying? Her coat is shiny, her weight is admirable and she’s conducting her daily foraging like any wild horse would. Might the clean-up crew be slow in coming because there’s something they know, and she knows, but we don’t?

So, for today, wild mare is our usher to other stories and other territories. And in return for her service, I’d like to take this chance to remediate her image. I’d like to shift her from an object of pity to an example of defied expectations. I’d like to employ her image—frozen on a field biologist’s trail cam—as an object of contemplation and curiousity that calls on us to wonder: what do we really know about what bodies can do? As well as how and why they do it?

This mare isn’t necessarily on death’s doorsteps. But her situation is certainly pointing to the underworld. Not the afterlife; but the underworld.

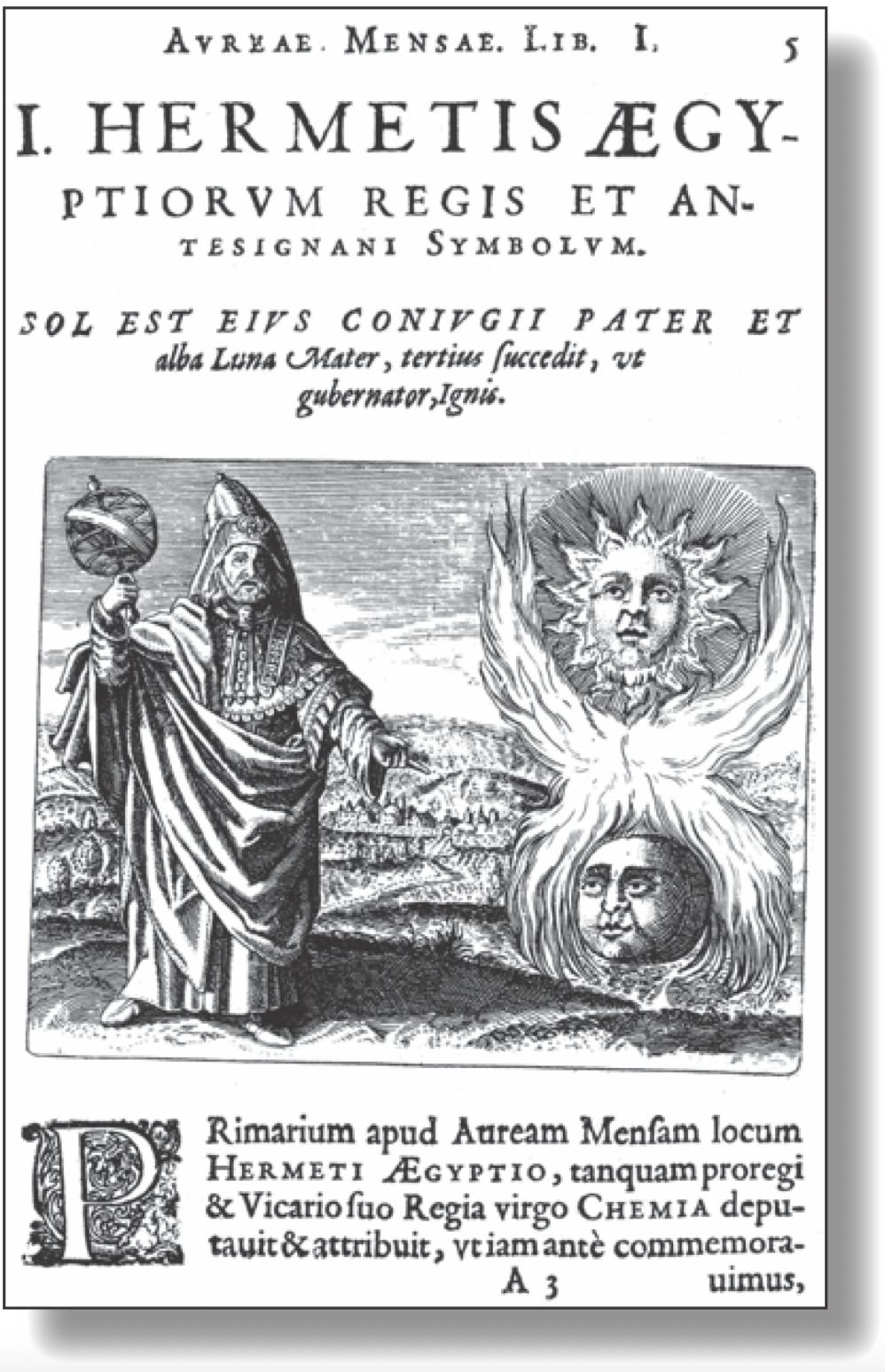

AS ABOVE, SO BELOW

Like the Hermetic maxim as above so below, I’m suggesting there’s a mirror world to the overculture, that exists beyond our conditioned perception. This isn’t the underground of criminal activities and deviant social circles for deviance’s sake. It’s a place one enters when the norming gets tough. It’s a place one enters when the norming is no longer (or never was) tenable. It’s a place where normative categories for naming and knowing cease to hold us in. And normative ways of “healing” cease to hold us together.

It’s the place we avoid with the help of multitudinous distractions and coping mechanisms available from normopathic culture—mechanisms that mask the symptoms normopathy itself has had a hand in causing (but has no interest in addressing). The underworld is where we fall when the coping mechanisms lose their efficacy. The underworld is where we fall when the coping mechanisms crap out.

Or something inside pushes back and says: passing for norm is more costly than meeting the pain of not passing. When something inside you performs this calculation, you are being initiated into an otherworld existence.

In its western esoteric context of late antiquity, as above so below served to signal the dualistic connectivity between the macrocosm and the microcosm. Between upper and lower dimensions of reality. Between the visible and invisible, the physical and non-physical, the outer and inner. In my deployment of the phrase, I’d also like to add (more on this in Part 2) the realms of the functional and dysfunctional, productive and unproductive, intelligible and unintelligible, doing and being, yes and no, open and closed.

The actions in one dimension cause effects in the other and there’s an understanding of inverse cosmic balance. One cannot operate solely in the above without consequences arising below—and vice versa.

Root to rise they say, that’s how one keeps their balance in multiple dimensions at once. But we are top heavy in our current culture and at risk of blowing over with the increasingly chaotic winds of change.

A STORY FROM THE UPPER WORLD’S SHALLOWER LAYERS

It’s over six years ago and I’m only a few years into offering alternative horsemanship services. My practice is still taking shape—still evolving out of the more traditional models of schooling I inhabited for decades before. But I’m also several layers deep into a number of underworld initiations. So, though I’m miles away from the subtle refinements I now practice, I’m still inclined to develop a horse only so far as their body will let me. I won’t load them with gear and gadgets that help me get my way. I won’t rush them through intimidation. I won’t sanction medical interventions that allow humans to push the bodily boundaries of their mounts. I won’t serve the training timelines of clients if they put be at odds with the horse. Even back then, there was space in my practice for the body to say no. There was space in my practice to let the NO root me into underworld realities to temper above-ground ambitions.

So there I am six years ago and a new client requests that I do a session with the companion horse to her main dressage mount. The companion is mostly an accessory. But the owner would like this mare to become a guest mount—a little sidepiece that her visitors can take out on joy rides.

Now, this little accessory hasn’t been doing much but field hangs for years and there are some suspected past injuries and ailments. But no matter, “it’ll just be trail rides”. Pleasure rides are a standard feature on almost all horses, aren’t they? “Just do a few sessions to make sure she’s safe for the guests”.

Well indeed, the mare (in her mid-to-late teens) has some stiff joints and laboured movement. Anyone who’s developed an equine body from scratch would not be surprised by these limitations given her history. It’ll take time to slowly work the rust out and to see what’s going on under the hood. I send the mare out on the lunge line at walk. After some start-stop debates that indicate she’s used to work being an argument, she finally begins to relax when she senses I’m here to serve her best interests.

She stretches her neck and loosens her gait. Her limbs grow incrementally more limber and her stride elongates every so slightly with each pass of the circle. I’m pleased. The mare is already seeking softness and I’m keen to let that slow and gentle pace do the work of further suppling.

If I ask too much now, I’ll give her unfit body reason to guard itself. Pain sensors will become heightened, large muscle groups will constrict, emotions will rise and her attitude will sour. That stride will return to its choppy state and I’ll have achieved nothing. Except, perhaps, the illusion that I am trainer shaped—walk like one, talk like one, move like one, push like one. And if I push like one I’ll have demonstrated my loyalty as an agent of the upper world—working in the name of go-go-go and now-now-now.

I explain to the client what I’m doing and why and suggest the slow approach is what’s best. I draw her attention to the micro-openings in the mare’s body and the soft expression in the mare’s face. I also show the reactivity, the brace, the pain face that arises when I become more insistent with my cues. The client looks unimpressed and perhaps suspicious. As if I’ve just pointed to the sky and said: “there, can you see angel Gabriel is smiling upon us? Stick with me and I will help you read these strange omens!”

She walks away silently and grumbles over her shoulder, “your money is in the cup in the barn”. She’s seen enough for today. We proceed like that for a few sessions in the weeks to come. I’m learning the mare’s edges and using them as my guide for when to ask, when to hold the course and when to back off my requests. The client rarely stays to watch.

I give her glowing updates about how the mare is responding to micro-communications and describe the tension deposits leaving her body and movement improvisations that have come to replace them. At the client’s request, I also begin mounted work. But old pain patterns return when I ask for trot, so I suggest this is an edge that needs tending. I continue to recommend slow development but my suggestion goes unacknowledged and there’s talk of an old friend coming for a forest ride. I reassure her we’re on the right track but encourage her not to be too quick in putting a stranger on the mare’s back or asking for much more than these therapeutic-style sessions for the time being.

From the look on the client’s expressionless face I consider what she hears. “When the black crow walks at night and its tail feather falls on a spruce branch, only then we will know that the true time has come.”

She stares at me blankly and I can feel her organizing what she’s about to say. I wonder if she’s finally understanding my style of work—different as it is from everything she knows.

“The farrier watched you work last week and he says she’s not moving her hind end enough.”

Not moving her hind end enough? By what measure? What is “enough” when you’re in your mid-to-late teens and you’ve just been pulled from a field and asked to work? Enough compared to what—your sporthorse? What the eff does your farrier know?

I’m deflated. The statement was made as an indictment of my training—presumably a reason to discredit me as messenger of the underworld. As if I didn’t know how to “get her hind end moving.” As if the entirety of what I was doing with this mare could be measured by that most tired of dressage phrases that is so misunderstood by most who use it.

One does not simply “engage their hind end.” Saying so implies there’s a button to push—and a mechanistic creature that will respond to such a simple signal. It ignores that engagement is the peak expression of a slow and complex process. It’s an act of “joining in”. And that joining requires connectivity. In a body that is stiff and uncoordinated, muscularly weak and often reacting to pain, connection involves gradually getting body parts to talk to each other. And this sweet thing’s body parts were finally starting to talk to each other! But that came to a screeching halt with this one statement. She stopped lessons shortly after that.

My concern wasn’t that they were incorrectly understanding hind end development or failing to see the graduated process of getting there. It’s the disinterest in the mare’s underworld reality—her pain, her fears, her physical limitations. It’s the suspicion and dismissal of someone who is trying to attend to these old and accumulated, dense and dark things instead of reflexively enforcing reproductions of the upperworld status quo.

It’s their insistence on judging her with upperworld criteria to evaluate her worth (as well as mine).

There are many who are only interested in bodies—of others or even of their own— insofar as they can milk above-ground activities for above-ground accolades or uses.

The upper world borrows from the underworld and rarely, if ever, pays back.

We have developed ourselves disproportionately in the above world, without establishing enough depth of root, enough exploratory curiousity, enough patience, enough pain literacy, enough acceptance of partial knowings, enough tolerance for uncertain futures, enough pressure resilience, enough night vision, enough echolocation, enough depth perception, enough liminal capacity, enough hybrid categories of thought, enough ambidexterity, enough existential agility, enough subterranean semiotics, enough endurance for the long haul.

In the above world, we’re conditioned to see the thing that is blocking our way as something that must be eradicated or avoided, instead of as THE WAY itself. We would be wise to cultivate a relationships with rogue forces that are—as we speak—eroding human-centred certainties with historic rapidity and opening us to more-than-human skillsets for traversing uncertain terrain.

That is, if we have enough underworld intelligence to see such events as skill building opportunities. Not hero skills; but humble skills.

Skills for navigating crisis, for meeting the material effects of falling outside of normal without being too quick to try and make it all better or turn our downfalls into redemption stories. Skills for being with bodies and beings that fail. Being with bodies and beings that fail to meet our expectations. Bodies and beings that underperform, deform, diverge, disease, depress and deviate. Bodies and beings that fall ill, fall victim, fall down below our threshold for sense making. Bodies and beings that fail to live up to our standards of perfection, of performance, of ability, of utility, of a life worth living. More importantly, the concept of the underworld is about pushing back against the criteria that construct our notions of failure altogether. The time has come to stop posturing as if we’re on top of life. When in fact, life is on top of us.

In PART 2, I’ll touch briefly on my own initiation into the underworld that started with a suddenly failing body and ended (or so I thought) with insights that birthed an entirely new approach to my inter-species relational practice. I, draw on Erin Manning’s “pragmatics of the useless,” Bayo Akomolafe’s concept of “the crack,” and the microbial agencies pursuing my gelding for months now to trouble my own linear urge to cleanly promise the underworld is but a pit stop on route to our latest personal growth narratives. I’ll propose that underworld events and subterranean visits are likely to become more frequent for us all. It’s time to stop resisting the gravitational pull of the underground.

Thank you for this. I wish more would embrace this underworld journey. To understand that in darkness we see most clearly. Looking forward to part two.

Another deep and insightful essay Shannon. And I think nature is not cruel, nature is always just being nature. It is filled with meaning and growth when we have eyes to see it, feel it , and offer our reflection to it.